In North Vancouver water comes out of the tap. You turn it on, and there it is. Cold, clean, safe, and only a little bit chlorinated and fluoridated. That’s true in most cities and towns.

For the rest of us the truth is that we each have a well. Wells also vary considerably from place to place and house to house. These days they’re usually drilled straight down into the earth until hitting water, after which a pipe and pump pull that liquid necessity from the earth.

So, as much to document what we have as to educate the city folks, here’s where our water comes from.

The picture at the very top is our well. It is a dug well. At some point a long time ago someone dug a hole deep into the ground. It’s about 20 feet deep, and four feet wide. Once the hole was dug they lined it all around with stones to keep it from collapsing. It’s really a lovey bit of construction. The actual water in the bottom, which seeps in from the ground around it, is about 8 feet deep right now.

Much, much later our well got a fancy concrete top end, and a wooden hatch to access it.

The end of the water line is right at the bottom of the well. From there is it runs up, and is buried for its journey across the yard and into the basement of the house. That water line connects to our pump.

The pump is old, and likely nearing the end of its life. From the pump the water flows through a filter. This mostly just blocks the heavy iron that we get, keeping the water clear instead of rusty. Our toilets, sinks, and clothing thank us.

Then it flows though our UV treatment, where really high intensity ultraviolet light blasts the living hell out of any bacteria and such that might be living in the well water. We just replaced the UV light tube in that, and it cost us about $120 for the new one.

What prompted all of this was our annual water testing. If you rely on a well for water you get it tested every year just in case something bad is in your water. When I lived in Sharon, Ontario we had a really big problem, and it took ages for someone to track our well problems back to an overflowing septic tank five doors up the road.

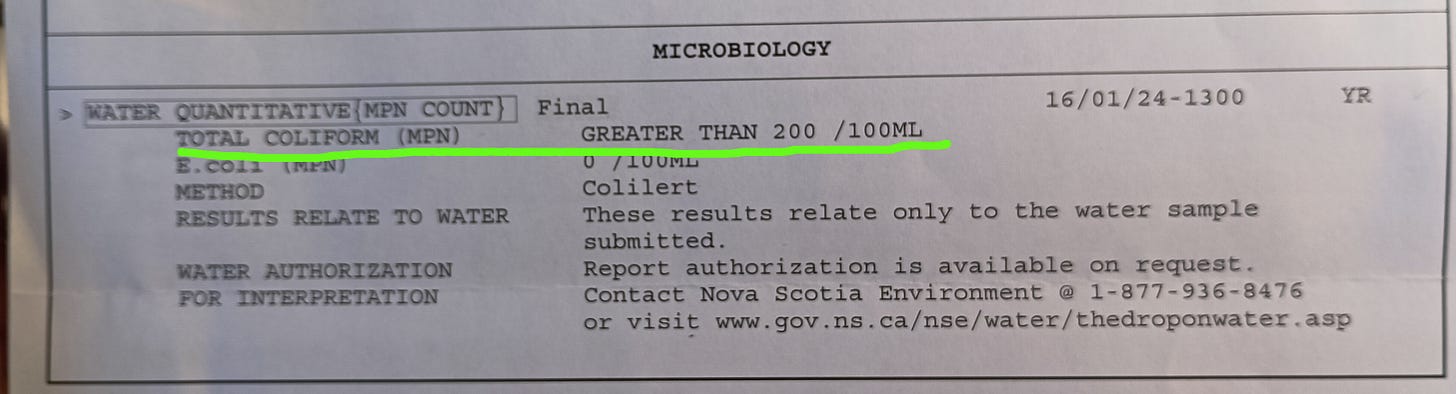

So I believe in testing, even though the local health authority charges for it. Here’s what came back.

Coliform bacteria is bad. It probably won’t kill you, but bad nonetheless. The attached advice from the local health people was to bleach (or “shock”) the well.

The instruction sheet was pretty good:

Dump the specified amount of chlorine bleach into the well, based on how big it is.

Run each tap in the house, one at a time, until you smell bleach, then shut it. Run the dishwasher and washing machine too.

Now that you know that all of your pipes are full of bleachy goodness, leave them be for twelve hours.

Next morning, run each one until it doesn’t smell of bleach, and run an outside hose a for a couple of hours until it seems that everything has been cleaned out of the system.

I now know roughly how long you can run your taps in our house before the well runs dry. By “runs dry” I mean: is empty, and there’s no water to be pumped out of it. And consequently I also now know how to prime the pump to get everything running again once the well has filled up again.

I also now know that between the Internet and talking to various people, there are actually at least a dozen different ways to shock your system, some taking more time, some less, and some ignoring the actual well entirely.

And all of which swear that they are the ones that know the truth about the matter.

And of course I know that no matter how terribly careful you are dumping three gallons of bleach into your well, at least one piece of clothing will have white patches tomorrow morning.

Next week we test the water again. Fingers crossed we can ignore it for another year.